There's a famous study about children and marshmallows that shaped how we think about success for decades. Researchers would put a marshmallow in front of a child and say: you can eat this now, or if you wait fifteen minutes, I'll give you two marshmallows. Kids who could wait supposedly had better self-control, which predicted everything from higher SAT scores to better health outcomes years later.

For years, we took this as proof that some people are just better at delaying gratification. They're disciplined. They have willpower. They make smart choices while others give in to temptation.

Then someone ran the experiment differently. Before the marshmallow test, the researcher would promise to bring better art supplies and either keep that promise (reliable condition) or break it (unreliable condition). The results were dramatic: kids in the reliable condition waited four times longer than kids in the unreliable condition.

The children weren't demonstrating different levels of willpower. They were making rational calculations about whether waiting was worth the risk. If the adult kept their promise before, waiting makes sense. If they broke it, eating the marshmallow immediately is the smarter choice.

This simple insight reveals something profound about how societies work: what looks like individual moral failure or poor character is often rational behavior responding to environmental conditions. And when those conditions change, so does rational behavior, even if the aggregate results are disastrous.

The Framework: A Diagnostic Tool, Not a Moral Judgment

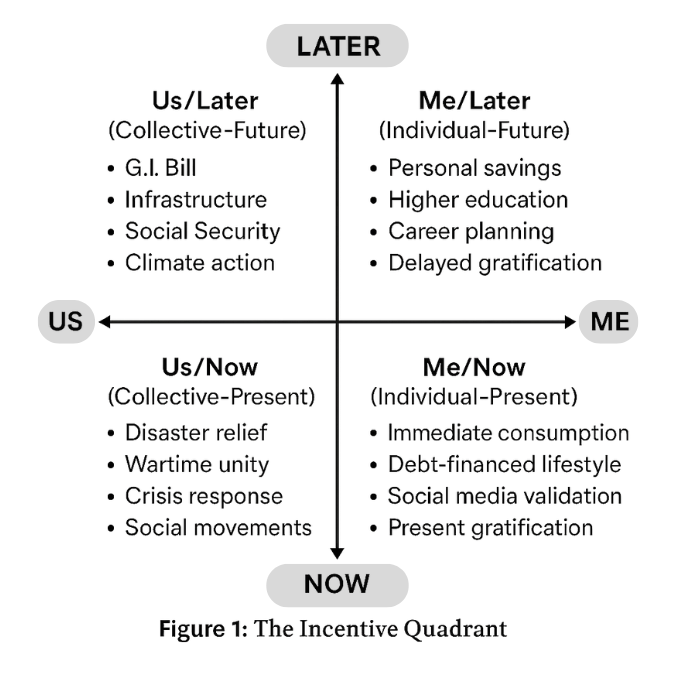

To understand how this plays out at scale, I developed what I call the Incentive Quadrant. It maps how individuals and societies make decisions along two critical dimensions: the social axis (Me versus Us) and the temporal axis (Now versus Later).

Before we go further, let me be crystal clear about what this framework is and what it isn't:

It is: A diagnostic tool for understanding why choices that look insane from the outside feel rational from the inside. A way to see what environmental conditions would need to change for better choices to become the rational ones. A language for analyzing behavior without immediately jumping to moral judgments about character.

It isn't: An excuse for bad decisions. A claim that people can't choose differently. A suggestion that understanding someone's logic means endorsing their choices. A way to avoid responsibility by saying "the system made me do it."

Rational doesn't mean smart. It doesn't mean good. It doesn't mean serving your long-term interests. It means internally consistent given your perceived reality. Understanding why something feels rational to someone is the first step toward seeing what would need to change for different choices to become rational, not an endpoint that excuses the current choices.

The Four Quadrants

These two dimensions create four distinct quadrants, each representing a different logic:

Us/Later (Collective-Future) is the logic of collective investment. This is building infrastructure that takes decades to complete, funding education systems whose benefits compound over generations, establishing social insurance programs, or addressing climate change. It requires believing that the collective will endure and that present sacrifice will yield future rewards worth having.

Us/Now (Collective-Present) is the logic of solidarity. This is disaster relief, wartime unity, crisis response, social movements demanding immediate change. It's reactive and cohesive, binding groups together against present threats or toward immediate shared goals.

Me/Later (Individual-Future) is the logic of personal ambition. This is pursuing difficult education, building a business from scratch, saving for retirement, any personal sacrifice and planning for individual advancement. It depends on a stable system where effort and delayed gratification are reliably rewarded down the line.

Me/Now (Individual-Present) is the logic of survival or gratification. In survival mode, it's the rational response to precarity: when you're worried about making rent, long-term planning is a luxury you can't afford. In gratification mode, it's prioritizing immediate pleasure: debt-financed consumption, social media validation, present comfort over future security.

The crucial insight: none of these orientations is inherently good or bad. Each makes sense under particular conditions. The question isn't which quadrant is virtuous, but which one matches the actual environment you're operating in—and whether that match is serving you well.

Rational Dysfunction: When Smart Choices Create Collective Disasters

This is where things get both interesting and uncomfortable. Rational dysfunction occurs when individuals making perfectly sensible responses to incentive structures collectively produce outcomes that undermine the system itself.

Consider the student asking for an extension on a paper because they're "not in the right headspace." Individually rational: why suffer through stress when you can request accommodation? The student has learned from childhood that expressing emotional distress often results in reduced expectations. Schools facing pressure (and potential liability) find it easier to accommodate than resist.

Is this student making a good long-term choice? Probably not. Are they developing the distress tolerance they'll need in professional environments? No. Could they choose differently? Yes. But given the incentives they face—accommodation works, pushback is rare, emotional discomfort feels intolerable—their choice makes internal sense.

Now multiply this across thousands of students. The aggregate result is an institutional environment where emotional comfort takes priority over developing distress tolerance. Students graduate without having learned to work through discomfort, enter workplaces expecting similar accommodation, and struggle when professional environments don't provide it. But each individual choice along the way was rational given the incentives in play.

Understanding this pattern doesn't mean we should accept it. It means we can see what needs to change: either the institutional incentives (stop rewarding accommodation-seeking) or the individual's capacity to handle discomfort (develop better distress tolerance), or both. The framework shows you where to target interventions, not whether intervention is needed.

The Vanderbilt Example: Three Generations From Fortune to Nothing

One of my favorite illustrations of this dynamic comes from the Vanderbilt family fortune. Cornelius Vanderbilt built one of the largest fortunes in American history through relentless work and ruthless business tactics, starting as a ferry operator and ending with a railroad and shipping empire worth roughly $200 billion in today's dollars.

His son William doubled the fortune through careful management and strategic investment, becoming the richest man in America. His grandson Cornelius III threw legendary parties at his Fifth Avenue mansion, married seven times, and died leaving a modest $1.5 million estate. By 1973, when 120 Vanderbilt descendants gathered for a family reunion at Vanderbilt University, not one of them was wealthy.

The standard explanation blames moral decline: the first generation builds through hard work, the second maintains through discipline, the third destroys through indulgence and weakness. But this misses what's actually happening through the Incentive Quadrant lens.

The founder experienced scarcity and understood that survival requires relentless accumulation. His Me/Later strategy (individual focus, future orientation) made perfect sense given his environment. Every dollar saved represented security against the poverty he'd escaped.

His children, raised in comfort but watching their father's obsessive work, concluded that wealth should be preserved and grown through careful management. Their Us/Later strategy (collective family focus, future orientation) made sense: they'd never known want, but they'd absorbed their father's anxiety about losing everything.

The grandchildren, born into established wealth with no memory of struggle, sought meaning beyond mere accumulation. Why prioritize saving when abundance is all you've known? Why fear poverty you've never experienced? Their shift toward Me/Now (individual focus, present orientation) was rational given their environmental reality.

Was the third generation making good choices? No. Could they have chosen differently? Absolutely. Were there Vanderbilt cousins who managed wealth better? Probably. But understanding why spending felt more rational than saving doesn't excuse the spending. It shows you what would have needed to be different—maintained scarcity mindset, institutional wealth management, different values transmission—for preservation to feel as rational as consumption did.

Each generation's strategy made sense within their context. The fortune dissolved not because the third generation was morally inferior, but because the incentive structures that created and preserved the wealth no longer operated. Remove the threat of scarcity, and behaviors that respond to scarcity disappear—unless you actively work to maintain them through other means.

Seeing It Everywhere Once You Know What to Look For

The Incentive Quadrant helps explain phenomena across every domain once you start looking. These aren't endorsements of the behaviors. They're explanations of why the behaviors persist despite being collectively destructive:

Public health struggles. The choice between the immediate pleasure of an unhealthy meal (Now/gratification) and the long-term benefit of good health (Later) is a classic delayed gratification problem. For individuals under cognitive load from economic precarity, the mental energy required to plan healthy meals, exercise, and resist temptation is taxed. The Me/Now focus prioritizes immediate comfort and stress relief over abstract, distant health outcomes. Not irrational at the individual level, but collectively producing the obesity epidemic. Solution: either reduce precarity (so people have bandwidth for planning) or make healthy choices easier than unhealthy ones (so they become the rational default).

Political gridlock. The persistent inability of political systems to address long-term challenges like climate change, debt, or entitlement reform is a manifestation of the Me/Now trap. The shortened time horizon (Now) incentivizes politicians to focus on short-term electoral cycles. Deep partisan fragmentation (Me/Them rather than Us) makes cooperation necessary for long-term solutions nearly impossible. Passing difficult legislation requires present sacrifice for future collective good, fundamentally at odds with the dominant logic rewarding immediate, tribal responses. Understanding this doesn't excuse gridlock. It shows you what needs to change: either lengthen political time horizons (different electoral systems) or reduce polarization (different media incentives), or both.

Consumer debt patterns. The widespread preference for immediate consumption financed by high-interest debt over long-term savings represents temporal discounting in action. In an environment of economic precarity and institutional uncertainty, the tangible pleasure of a purchase now can feel more rational and reliable than the abstract promise of financial security later. The scarcity mindset reinforces this: managing daily finances leaves little bandwidth for complex retirement planning. These are terrible financial choices. Understanding why they feel rational is step one toward changing either the environment (more stability) or the individual's capacity to override impulses (better financial education designed for scarcity mindsets).

Social media dynamics. Platform architecture perfectly reflects Me/Now logic. Designed to deliver instant gratification (Now) through likes, shares, notifications. Content is ephemeral, focused on fleeting trends and immediate reactions. Simultaneously promoting hyper-individualistic focus (Me) through personal brand curation, identity performance, and algorithm-driven filter bubbles reinforcing existing worldviews while isolating from different perspectives. This is destroying our collective capacity for sustained attention and reasoned discourse. Understanding the incentive structures doesn't make it okay. It shows you what needs to change: different platform design, different business models, different regulatory frameworks.

Educational credential inflation. Students rationally pursue degrees not because education improves competence, but because credentials signal reduced hiring risk to employers. Employers rationally demand degrees not because they predict performance, but because they shift liability (hiring the credentialed candidate who fails is defensible; hiring the uncredentialed one who fails is questionable judgment). Universities rationally inflate grades to improve student satisfaction and rankings. Each actor is rational; the system produces credential requirements disconnected from actual capability. No individual is wrong to play the game as structured. The game itself is broken and needs restructuring.

The Migration That Explains Everything

Here's what I'm arguing in my book The Perfect Storm: Western democracies have undergone a fundamental migration within the Incentive Quadrant over the past half-century. Post-war America operated predominantly from Us/Later: high institutional trust, strong social cohesion, massive collective investments in infrastructure and education, individual planning for predictable futures.

Contemporary America increasingly operates from Me/Now: short-term thinking, fragmented social identity, eroded institutional trust, consumption-driven economics, immediate gratification through technology, political systems responsive to outrage rather than deliberation.

This didn't happen because we became less virtuous or more selfish. It happened because the environmental conditions that made Us/Later rational were systematically dismantled and replaced by conditions making Me/Now the more intelligent response to immediate incentives.

When society's institutions prove unreliable (like the researcher who broke their promise), citizens rationally shift from Later to Now. When the social fabric tears and trust erodes, they rationally shift from Us to Me. The aggregate result is a society operating under fundamentally different logic than the formal structures were designed to support.

Are these good shifts? No. Could individuals resist them? Some can, with effort. But the framework helps us see that telling people to "just plan long-term" or "just think collectively" without addressing why those strategies feel irrational is like telling the kids in the unreliable condition to "just wait for the second marshmallow." You're not wrong that waiting would be better if the researcher is reliable. You're wrong that willpower alone overcomes learned distrust.

The Marshmallow Test, Societal Scale

Remember those kids and the marshmallows. The lesson wasn't about willpower. It was about rational calculation under uncertainty. When adults prove unreliable, eating the marshmallow immediately is the smart move given available information.

Scale that insight up to society. When institutions repeatedly break promises, when planning for the future feels futile, when cooperation goes unrewarded, when long-term thinking is punished and short-term reactions are incentivized: the rational response is to focus on Me/Now. Not because we're weaker or more selfish than previous generations, but because we're just as rational while facing different incentive structures.

The uncomfortable truth is that much of what we call social dysfunction is rational adaptation to changed conditions. The student demanding accommodation learned that strategy works. The politician playing to outrage learned that nuance doesn't. The parent choosing permissiveness learned their child's immediate happiness matters more than distant character development in their social environment. The worker staying in a safe job rather than taking entrepreneurial risks learned that credentials matter more than capabilities.

All rational. All individually defensible given current incentives. All collectively producing outcomes that undermine the systems making those individual choices possible. And simply understanding this doesn't make the choices good or excuse them. It shows us what we'd need to change for better choices to become rational: rebuild institutional reliability, restore social trust, lengthen time horizons, reduce precarity.

This is the perfect storm: when rational individual adaptation to changed incentive structures creates collective dysfunction that further degrades the conditions making longer-term, more collective thinking possible. A self-reinforcing cycle pulling society deeper into the Me/Now quadrant, making it increasingly difficult to execute the Us/Later projects that might reverse the trajectory.

What This Framework Lets You Do

Understanding the Incentive Quadrant doesn't immediately solve problems. But it changes what you're looking at:

Instead of seeing moral decay, you see rational adaptation to incentive structures. Instead of blaming individuals for choices that make sense given their environment, you can examine the environmental conditions producing those incentives. Instead of treating symptoms with willpower lectures, you can identify what structural or psychological changes would make better choices rational.

The question isn't whether people should make better choices. The question is: what would it take to create environmental conditions where better choices are also more rational choices? Where waiting for the second marshmallow feels smart because researchers reliably keep their promises?

That's what The Perfect Storm explores: how we got here, why the migration from Us/Later to Me/Now was so systematic, and what understanding these incentive dynamics suggests about possible paths forward. Not through moral exhortation or telling people to have more willpower, but through rebuilding the environmental reliability that makes waiting for the second marshmallow the smart move again.

Or, when environmental reliability can't be rebuilt, through developing frameworks and support systems that help people make better choices even in unreliable environments. Not by denying the environment is unreliable, but by acknowledging it and building better strategies for navigating it.

The framework is a tool. What you do with that tool—whether you use it to excuse dysfunction or to target interventions more precisely—is up to you.

This essay introduces concepts from my forthcoming book The Perfect Storm: A Systems Analysis of Civilizational Incentive Reversal, which examines how Western democracies shifted from collective, future-oriented decision-making to individualized, present-focused logic over the past half-century. The book traces this migration through parenting practices, technological platforms, institutional responses, economic forces, and their convergent effects on contemporary politics and society.