Taylor is a 31-year-old nurse with four kids. She's three months behind on her $3,185 mortgage. Her credit cards are maxed. The IRS wants $3,000 in ten days. And she just spent $950 on a bulldog because she refused to adopt from the Austin Animal Shelter after her sister's dog once lunged at her child.

When confronted about this on Financial Audit, she cycled through explanations: her difficult divorce, the transition period, never learning to budget independently. Each justification met with escalating frustration from host Caleb Hammer. To the audience, she looks insane. To me, she looks perfectly rational.

Not making good choices. Not choices I'd defend. Not choices serving her long-term interests. But rational given the incentive structure she's operating within. Understanding why something feels rational to someone doesn't mean it's smart or that they couldn't choose differently. It means we can finally see what would actually need to change for different choices to become possible.

The Framework: A Diagnostic Tool, Not an Excuse

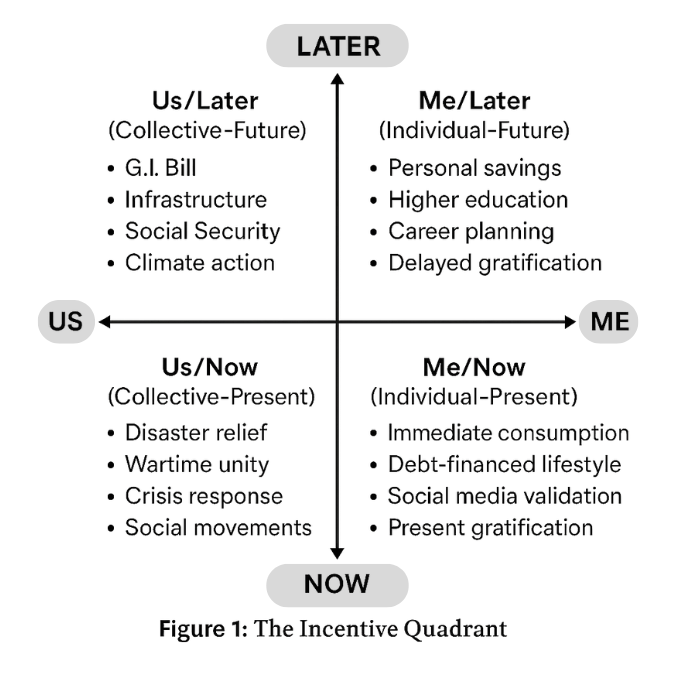

This analysis uses my Incentive Quadrant framework, which I explore more fully in Understanding the Incentive Quadrant. It maps how individuals make decisions along two dimensions: the social axis (Me versus Us) and the temporal axis (Now versus Later). These create four distinct orientations, each rational under different environmental conditions.

Here's what this framework is and isn't:

It is: A diagnostic tool for understanding why choices that look insane from the outside feel rational from the inside. A way to identify what environmental conditions would need to change for better choices to become the rational ones.

It isn't: An excuse for bad decisions. A claim that people can't choose differently. A suggestion that understanding someone's logic means endorsing their choices. Rational doesn't mean smart. It means internally consistent given their perceived reality.

Think of it like a doctor diagnosing why someone keeps reinjuring the same muscle. Understanding the biomechanical pattern doesn't mean the injury is inevitable or that physical therapy won't work. It means you can finally target the actual problem instead of just telling someone to "try harder not to get injured."

The Trust Collapse Pattern

Take Dakota, the 23-year-old furry making $65,000 annually as a server. He has undiagnosed (later diagnosed) BPD, refuses medication, and spent $1,000 at Neiman Marcus the day before filming. When Caleb pushes him on the contradiction between knowing better and doing worse, Dakota admits: "I like being choked out by life."

Dakota can calculate compound interest in his head. He understands budgeting. But when you don't trust your future self to maintain discipline without medication, when your brain chemistry makes emotional regulation through spending feel necessary, when tomorrow's stability feels less reliable than today's dopamine hit: Me/Now becomes rational. Not good. Not healthy. Not serving his interests. But rational given his perception that he can't trust himself tomorrow.

The solution isn't yelling at Dakota to save for retirement. It's addressing why he doesn't trust his future self (untreated BPD). The spending is downstream of that distrust. You can't budget your way into trusting yourself any more than you can logic your way out of bipolar disorder.

Or consider Camila, who's using 85% of her income to service pay advance apps while planning to buy a house with her boyfriend of one year. Not because she wants a house. Because, as she explicitly states, "if you're renting it gives him a door to leave." She's weaponizing debt as relationship insurance.

This is a terrible strategy that will absolutely backfire. Understanding why it feels rational to her doesn't make it less terrible. She doesn't believe the relationship survives without financial entrapment. Every payday loan serves that function. The spending isn't the pathology. The inability to trust relationships is. And until that changes, no amount of budget lectures will stick because she's optimizing for a different goal than financial health: she's optimizing for relationship control.

Understanding someone's internal logic is not the same as validating their choices. It's about seeing what actually needs to change rather than treating symptoms while the disease festers.

When Institutions Prove Unreliable

Natasha and Oscar, the Phoenix couple with $133,000 in debt, are DACA recipients brought from Mexico as children. Their work permits renew every two years. Oscar grinds 60-hour weeks in construction at $31/hour. They spent $2,800 to see Messi play soccer, $4,500 on Shakira concert tickets, $800 on a Deadpool costume worn once.

I don't think these were good choices. But I understand why they felt rational: when your legal status depends on biennial government decisions, when your ability to work hinges on political winds, when institutions feel fundamentally unreliable, why optimize for a Later that might not exist?

They're making memories while they can, spending on experiences that can't be repossessed, prioritizing now because Later feels precarious. Are there better strategies even given their uncertainty? Absolutely. Would an emergency fund serve them better than Messi tickets? Yes. But telling them to "just save" without addressing the underlying uncertainty is like telling someone with anxiety to "just relax." It misses the actual problem.

What they need isn't budget discipline. They need either: (1) immigration stability that makes ten-year planning rational, or (2) therapy/support to navigate planning under uncertainty better, or (3) a financial framework explicitly designed for precarious legal status rather than one assuming institutional stability.

The Avoidance Economy

Then there's Anna and Paul, the Indianapolis couple carrying $45,000 in consumer debt while sitting on $150,000 in equity in a house Anna's parents live in rent-free. Her parents contributed $4,500 to the down payment in 2016; her father now demands all equity if they sell. Anna acknowledges he's emotionally abusive. She won't have the conversation.

Every uncomfortable financial decision—the $2,800 Universal Studios honeymoon, the $1,200 cruise for a friend she had a falling out with before the trip, the $4,000 Christmas when they budgeted $1,500—serves a clear function: avoiding conversations she doesn't trust herself to navigate. When she's finally cornered on the parent house situation, she cries about not knowing "how to do that without losing my mom." Then walks out temporarily.

This is a terrible way to live. It's destroying her financial future. Understanding why she does it doesn't make it less destructive. The spending buys relief from situations she can't face. Until she can face those situations (therapy, boundary work, whatever), no budget will stick because she's using spending as an emotional regulation tool.

The difference between my analysis and Caleb's is this: I'm not saying "therefore we should accept Anna's spending." I'm saying "therefore we should recognize Anna needs therapy, not a spreadsheet." Trying to fix her spending without addressing her conflict avoidance is like trying to treat a broken leg with pain medication. You're not wrong that she's in pain. You're wrong about the intervention.

Why the Advice Fails (And What Would Actually Work)

Caleb's prescription is always the same: create a budget, stop spending on discretionary items, sacrifice now for Later stability. It's Us/Later logic applied to Me/Now lives. The math works on spreadsheets. It fails in implementation because the environmental conditions that make Later rational don't exist for these guests.

What would actually help isn't moral lectures. It's this:

Dakota needs: Medication that makes his future self trustworthy. Not because he's a bad person, but because untreated BPD makes planning impossible. Then he needs a budget that accounts for his actual brain chemistry, not one designed for neurotypical brains.

Camila needs: Therapy addressing why relationships feel unsafe without financial entrapment. Then a recognition that buying a house with someone you don't trust is trying to solve a relationship problem with a financial weapon that will backfire catastrophically.

Natasha and Oscar need: Either immigration stability making ten-year planning rational, or help developing financial strategies specifically for precarious status. The current advice assumes stability they literally lack.

Anna needs: Boundary work and trauma processing so conflict doesn't feel existentially dangerous. Then she needs to recognize she's spending thousands buying temporary relief from feelings that will return until she addresses them.

The spending is symptom. Distrust is disease. Budget advice treats symptoms while cameras roll.

This is why understanding the Incentive Quadrant matters: it shows you what actually needs to change. Not "try harder." Not "have more discipline." But specific environmental or psychological shifts that would make better choices rational instead of requiring heroic willpower to override rational responses.

Why We Watch (And What That Reveals)

Financial Audit works because Me/Now optimization combined with high income feels deliciously "deserve to be judged." These aren't people trapped by poverty; they're people with resources making catastrophically shortsighted choices. The audience gets to feel superior without guilt about punching down.

But that entertainment value depends on maintaining a specific narrative: these people are stupid, undisciplined, morally deficient. Once you see them as rational actors adapting to unreliable environments, the schadenfreude shifts. Suddenly you're watching someone tell people to trust systems they've learned not to trust, to plan for futures they have good reason to doubt, to rely on stability they've never experienced.

Does this make their choices smart? No. Does it mean they couldn't choose differently? No. Does it mean we should stop expecting them to make better choices? Absolutely not.

What it means is this: telling someone to "just save" when they don't trust tomorrow is as effective as telling someone with clinical depression to "just be happy." You're not wrong that being happy would be better. You're wrong about the intervention.

The Pattern You'll See Everywhere

Watch a few episodes with this framework in mind. You'll start seeing it: every guest clustered in Me/Now for identifiable reasons. Trust broken somewhere—in themselves, in relationships, in institutions, in the future. Rational adaptation to that broken trust manifesting as spending that looks insane until you understand the logic. Still insane. Still destructive. But understandable.

Savannah, the unemployed 27-year-old who won't spend ten minutes applying for Medicaid she'd 100% qualify for, choosing instead to catastrophize about American fascism while planning to flee to Europe. She needs anxiety treatment, not budget lectures.

Sierra and Jordan, the engaged couple spending $200-300/month on Fortnite skins while using payday loans for rent. They need to confront what they're avoiding through gaming, not another spreadsheet showing why paying rent before buying digital costumes is smart.

Each one rational given their internal logic. Each one making choices that will absolutely destroy them. Each one needing something other than what they're getting on camera.

This is rational dysfunction: when individually understandable responses to perceived environmental conditions create disasters that make those conditions worse, which reinforces the responses, which creates more dysfunction. A self-reinforcing cycle where everyone is making sense to themselves while collectively spiraling.

And we watch it twice weekly, judging the individuals while missing that the show's entertainment value depends on maintaining the very misunderstanding that prevents solutions. That's the real show.

A Note on Using This Framework

If you're reading this and recognizing patterns in your own life, here's what to do with that recognition: understanding why something feels rational to you is not the same as accepting it should stay that way. It's about seeing clearly what would need to change—in your environment, your support systems, your mental health, your relationships—for better choices to feel rational instead of requiring constant willpower to override your instincts.

This framework isn't about excusing yourself. It's about targeting the actual problem instead of beating yourself up for symptoms while the disease continues.

Related Reading:

This analysis applies the Incentive Quadrant framework from my upcoming book The Perfect Storm. I explain the Incentive Quadrant more fully in Understanding the Incentive Quadrant.